“Forget about the disgraceful creature you actually are; this is how you should be; and to be this idealized self is all that matters. You should be able to endure everything, to understand everything, to like everybody, to be always productive.”

If this quote sounds a bit harsh, it should. This quote from Dr. Karen Honey’s book Neurosis and Human Growth says out loud what many of us feel inside. What Dr. Honey called “the tyranny of the shoulds” is the idea that we often weigh ourselves down with “should statements” that tell us how we should be rather than acknowledging our reality as it is now. Examples include:

- “I should be doing more.”

- “I should already have a job.”

- “I should be able to handle this.”

- “I shouldn’t be struggling.”

As Dr. Honey explains, we rarely create our own should statements. They come out of overt and implied messages about how we should be from our from family, friends, teachers, bosses, social media, and our larger society. For example:

- “I should make my bed — my parents always said so.”

- “I should get good grades — my teacher said I need them for college.”

- “I should smile more — that guy said I look prettier when I smile.”

Even if some of these statements are factually correct (“grades affect college admissions”), they still come from someone else’s agenda, not necessarily the client’s authentic goals.

As a practitioner, you can help your client move past these should statements by creating achievable goals based on what they want.

Step 1: Shift From “Should” to “Want”

When you ask someone what they should do, the answer is almost always pressure-based. When you ask someone what they want to do, the answer becomes hope-based. For example:

- “Do you like having a clean room? If so, I can help you get organized.”

- “Do you want to go to college? If yes, let’s talk about what helps you get there.”

- “Do you want to frown? That’s your choice, and what that guy said was mean anyway.”

This shift does three important things:

- It reduces shame

- It restores the person’s autonomy

- It helps the person’s brain move from panic to problem-solving

When someone is depressed or anxious, this shift can feel enormous.

Step 2: Turn Wants Into Small, Achievable Goals

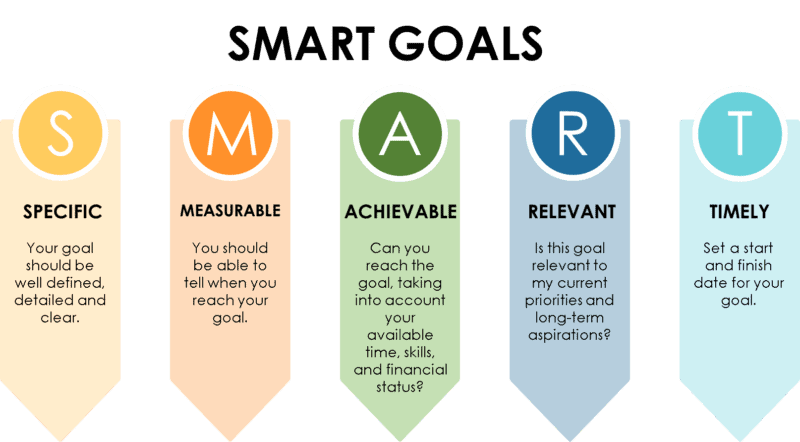

People in crisis need goals that feel safe, clear, and manageable. This is where SMART goals can help as long as they’re used gently. We’re not aiming for productivity. We’re aiming for emotional safety, realistic expectations, and attainable steps.

SMART goals are:

- S — Specific: “Update the work history section of my résumé.”

- M — Measurable: “Spend 10 minutes today.”

- A — Achievable: Not overwhelming or perfectionistic.

- R — Relevant: Connected to what they want.

- T — Time-bound: A small timeframe, like 10–20 minutes or one simple task.

Example transformation:

Should-statement:

“I should be applying to 20 jobs a week.”

Want-statement:

“I want to move out eventually, so I want to start looking for work.”

SMART goal:

“This week, I’ll identify two jobs I’m interested in. That’s enough for now.”

Should-statements create shame and fear. SMART Goals create choice and direction. SMART goals are not affective if used to pressure clients. Instead, they are most effective when used to create structure and hope.

Step 3: Use “Yes, And…” to Support the Shift

“Yes, and…” pairs perfectly with goal-setting to create psychological safety and a sense of collaboration. For Example:

Client: “I should already have a job.”

Practitioner: “Yes, it makes sense you feel behind. This is overwhelming, and we can start with one small step you choose. What feels doable?”

Reflection Exercise: Amy

Take a moment to pause and consider the scenario below. You can reflect quietly, write a few notes, or skip this section if now isn’t the right time.

Amy is a young woman recently out of college. She has a degree in fine arts and feels unsure about what to do next. Amy shares:

“Everyone told me I should go to graduate school, but I’m so burnt out I can’t focus. I should get a job so I can move out. All my friends already have.”

- What expectations or “should” statements seem to be driving Amy’s distress right now?

- How might a “yes, and…” approach help acknowledge Amy’s reality while opening space for additional possibilities?

- What kinds of affirmations could reflect Amy’s strengths, values, or experiences without dismissing her exhaustion?

Remember to notice what you’re thinking and learning. Take a break if you need one.

When you’re ready, continue to Burnout Prevention for Practitioners.