As a career advisor to people with disabilities, I’ve learned something the hard way: there is a billion-dollar industry built around selling people insecurity. An IBISWorld industry report shows that job search sites in the U.S. are worth an estimated $18 billion.

Each of these services push a simple idea:

Get the skills → write the perfect résumé → ace the interview → get the job.

It sounds scientific. It sounds formulaic. But once they sell the formula, they also sell the fear that you can’t pull it off on your own.

“Worried about your résumé? Pay us $1,000 and we’ll fix it.”

Practitioners know the truth:

- You can have a decent résumé and get hired. You don’t need a perfect one.

- Timing, luck, labor market trends, disability-related barriers, and human judgment play huge roles.

- Real life is full of variables that no formula can predict.

This isn’t just true of employment. Housing, transportation, healthcare, relationships — most major goals are shaped by timing, resources, and systemic barriers.

Clients don’t need a perfect formula. They need clarity, compassion, and a realistic path forward.

This is where the Six Steps to Success begin.

Step 1: Acknowledge the Situation

Many practitioners are natural fixers. When someone is struggling, our instinct is to jump in, offer solutions, and solve the problem immediately, but the first step is to slow down and understand what the client’s actual priorities are right now.

If someone is facing eviction, can’t afford medication, or is having panic attacks every day, they are not going to be receptive to self-esteem work, career planning, or long-term goals.

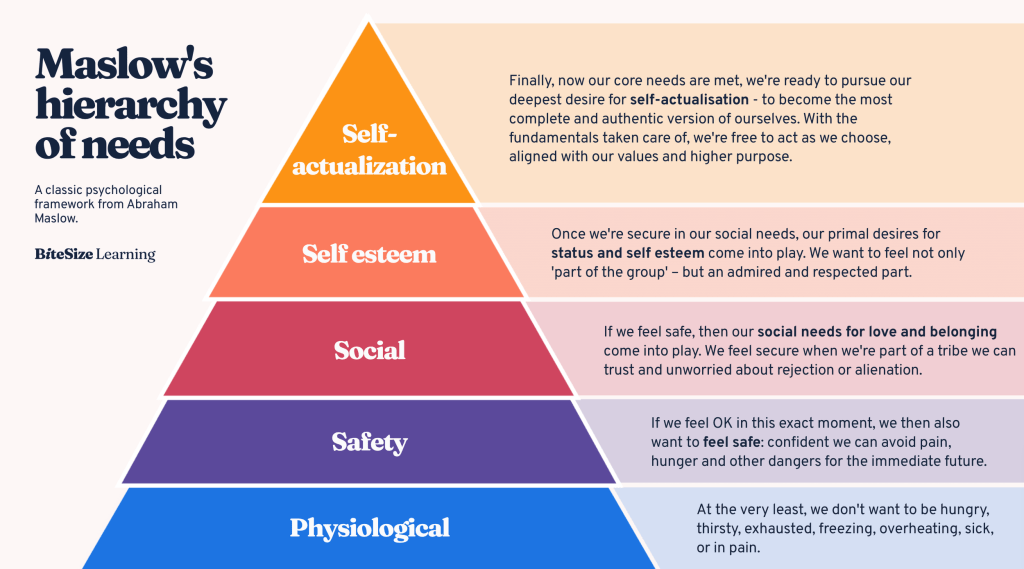

The image below from BiteSize Learning is Maslow’s famous Hierarchy of Needs. This pyramid reminds us that people must have safety and stability before they can focus on higher-level goals. You can read more about Maslow’s Hierarchy on BiteSize Learning’s website.

When you start working with a new client, it’s important you start by ensuring all their essential needs are being met:

- Do they need financial support?

- Are there medical or mental health needs that aren’t being met?

- Is there an immediate crisis that must come first?

Once you understand the situation, reflect it back so the client feels seen and supported:

“It sounds like you’re really worried about losing your housing. If I were in your position, I’d be losing sleep too. Is that what’s going on for you?”

This simple step validates their reality, reduces shame, builds trust, and creates psychological safety without risking slipping into clinical territory. You’re acknowledging the situation, not analyzing it, not interrogating it, and not doing therapy.

Validation is not agreement. Validation simply communicates, “Your feelings make sense in context.”

Step 2: Break the Process Into Steps

When someone is overwhelmed, even simple tasks can feel impossible. One of the most supportive things you can do is lay out the path in small, clear steps.

For example:

“First, we’ll look at your skills to see what fits. Then we’ll build your résumé together. After that, we’ll practice interview questions. Once that’s ready, I’ll help you find openings and set up job alerts.”

In this example, you’re not making promises or guaranteeing outcomes. You’re reducing uncertainty so the client can breathe again.

Structure lowers anxiety. It also helps the client understand that they don’t have to solve everything at once.

Step 3: Correct Myths and Misconceptions

Clients in crisis often carry beliefs that increase shame or hopelessness. Gently correcting these misconceptions helps them conserve energy for what truly matters. For job seekers, common examples include:

Myth: “Short-term jobs make me look bad.”

Reality: Almost everyone takes a temporary or “pass-through” job at some point. Employers understand.

Myth: “It shouldn’t take me this long to find a job. I must be doing something wrong.”

Reality: Job searches routinely take several months, especially for people with disabilities.

Myth: “I shouldn’t do anything but apply for jobs until I get one.”

Reality: The numbers game rarely works. Volunteering, taking classes, and going to networking events are much more useful and boost your mental health.

Correcting myths is not about confronting or challenging someone. It’s about relieving unnecessary pressure

Step 4: Create a Plan With a Realistic Timeline

People in crisis often say things like “I need a job now!” Your role is to gently ground the timeline in reality. For example:

“I hear how urgent this feels. The hiring process usually takes three to six weeks. Let’s talk about how to get you through the next few weeks while we work on this together.”

We often talk about fight-or-flight, but we can also freeze. Procrastination during crisis is not laziness. it’s survival. If someone is stuck in freeze mode, you can:

- Break tasks into small pieces

- Set gentle, realistic check-in points

- Do hard tasks with the client when needed

- “Let’s fill out the first page together right now.”

- Reinforce that needing help is normal, not a moral failing

Planning is not about pushing productivity. Planning is about creating psychological safety.

Step 5: Set Effective Boundaries

Boundaries are essential for safe, ethical, non-clinical practice. Effective boundaries protect you, the client, and your organization. They also prevent dependency, a common but unintended consequence when clients are in crisis. Examples of healthy boundary setting techniques are:

- Do not complete tasks for the client, but do them with the client if they are overwhelmed.

- Do not share personal phone numbers or connect on social media. Provide resources for the client if they go into crisis during nonworking hours.

- Do not allow communication outside professional channels.

- Do not perform therapeutic techniques or ask unnecessary personal questions.

Be clear and proactive from the beginning. Let the client know your organization’s policies and why they matter. For example:

“I know a lot of people like to connect on social media. Let me explain our organization’s policy and how to reach me in the best way.”

Boundaries are not barriers. They are guidelines that help clients build independence and maintain dignity.

Step 6: Encourage Connection & Peer Support

Crisis narrows a person’s world. People often feel isolated, ashamed, or convinced that no one else understands what they’re going through. By connecting your clients to peer and community supports, you can help:

- Reduce isolation

- Provide emotional encouragement

- Share resources and leads

- Normalize struggles and reduce shame

- Offer role models who have faced similar challenges

Peer groups may include:

- Support groups

- Disability ERGs (Employee Resource Groups)

- Online communities

- Advocacy groups

- Classmates, alumni, or training program cohorts

You don’t need to create or run these groups. Simply helping clients connect to community can be transformative.

Social connection is one of the strongest predictors of psychological resilience.

Reflection Exercise: Denise

Take a moment to pause and consider the scenario below. You can reflect quietly, write a few notes, or skip this section if now isn’t the right time.

Denise is a woman in her mid-50s who was recently laid off. She has enough savings to cover one more mortgage payment, with very little left after that. Denise describes having daily anxiety attacks and says she can’t start a job application without panicking that she will end up homeless.

- Looking at Denise’s situation through the lens of immediate needs, what concerns seem most pressing right now?

- In the moment, what kinds of responses or supports might help reduce her anxiety enough to create a sense of stability?

- How might acknowledging Denise’s fear about housing help create space for gradual steps toward her job search, rather than forcing reassurance or urgency?

This reflection is intended to explore how practical support, emotional validation, and realistic planning can work together without minimizing risk or distress.

Remember to notice what you’re thinking and learning. Take a break if you need one.

When you’re ready, continue to Using OARS in Non-Therapeutic Settings